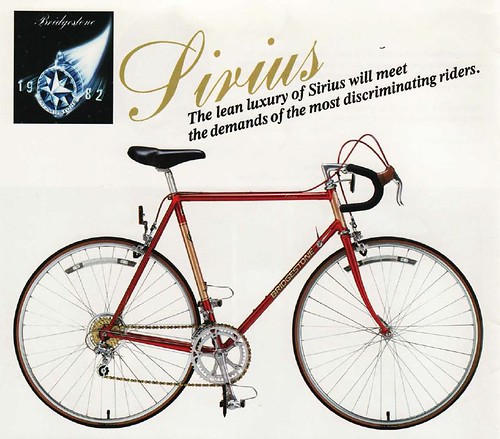

Completed Bridgestone Sirius bike in Madison building garage (where I work)

Completed Bridgestone Sirius bike in Madison building garage (where I work)I bought the frame, fork and bottom bracket on eBay for a 1982 Bridgestone Sirius road bike. It is a lugged steel frame, size 56 cm. The frame was like 85 dollars plus shipping. The paint is in better shape than the seller's photo showed it on eBay.

Nitto Olympiade handlebars, purchased on eBay

Nitto Olympiade handlebars, purchased on eBayI was not going to try to create a "PC" (period correct) 1982 bicycle - I wanted to see if I could buy and assemble a pleasing ride with components from various years for around $500 or so. (The joke was that for $500 I would put together a bike that I could easily sell for $350.)

Still, some things I did more or less PC - since the bike requires a quill stem for the threaded headset, I got Nitto Olympiade handlebars that are similar to what the bike came with (it had Nitto Universiade bars - close enough). I found someone selling these handlebars along with an SR stem (same period) at a good price (around 25 dollars for both) and stopped looking for the Nitto Technomic A stem the thing came with.

View from the rear - "flamboyant red" paint (per catalog)

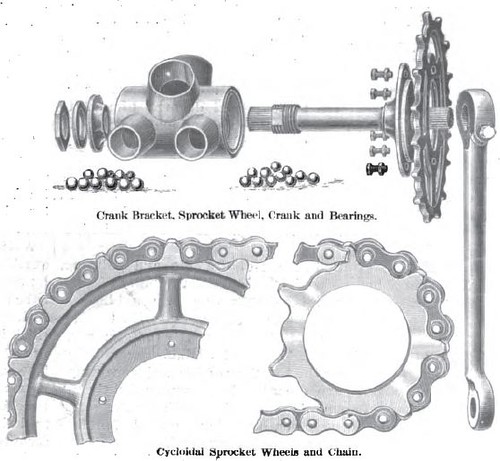

View from the rear - "flamboyant red" paint (per catalog)I got a Shimano 1055 series 105 group, although it didn't include the cogs (in back). So the brakes, brake levers, the stem shift levers, front and back derailleurs, and cranks and rings are all Shimano 105 from 1990 give or take. Intended to work with seven cog cassette. (The bike came with a six cog freewheel and most of what is now Shimano was originally SunTour.) The cog and ring tooth numbers are completely different than what this had originally -

Before - front, 52 x 42 teeth; now 53 x 39 teeth

Before - back, 14, 16, 18, 21, 24, 28 teeth; now 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 24, 28 teeth

So nominally this makes it faster. Also, it came with 25 mm tires and these are 23, but now of course people are all over the place as to whether narrower tires are faster or not.

Seven cogs should be enough

Seven cogs should be enoughSome things I bought new. The Shimano HG-70 cassette (with seven cogs) I bought new. The bike was sold originally with six cogs and apparently the "standard" was to have a space for the rear wheel 126 mm wide - when the increase was made to eight cogs (and now up to 11) the typical (or "standard") width was increased to 130 mm. So I had to buy a 4 mm spacer so that the set of seven cogs don't have too long (big) a cassette space to occupy (and slide back and forth - not good!). I decided not to try to find a 126 mm wide wheel so I simply spread the 126 mm wide opening of the rear stays to force in the 130 mm wide wheel with cassette. Four mm is not a problem for this "brute force" approach, it seems. Or so people advise on the Internet. So far so good.

I also bought a new aluminum seatpost and a (relatively) cheap new seat (but in red to match the paint!). I mismeasured, thought the opening was a standard 27.2 mm and bought a seatpost that didn't fit. Had to buy a 27.0 mm diameter seatpost - it fits. Not terribly attractive, but the choices in this size were few. In fact, I was a little concerned until I did find one that there was no such thing and that for lack of a seatpost the bike was going to be unfinished.

I got a new SRAM 870 chain. This is a chain intended for use with either 7, 8 or 9cogs (which are all the same width, it seems). Compared to a ten speed chain, it looks incredibly wide, which is sort of funny (to me).

Italian cut head lug (according to the 1982 catalog)

Italian cut head lug (according to the 1982 catalog)The frame is ChroMo tubing with Tange steel lugs. The headset is also from Tange.

The shift levers look more "old school" than they really are - the right one is actually "variable" - you can choose between indexed shifting or friction shifting. I have been using the indexed shifting option and it works well. The left one is friction shifting for the front derailleur.

I found brake and shift lever Shimano cable "kits" rather than buying lots of cable and housing and cutting to length. This worked fine, which surprised me for some reason. Some Jagwire replacement cables are pretty expensive but these were less then eight dollars each.

The wheels are new - Shimano R500 wheels that I found on sale (Presidents Day holiday) for $150 with free shipping. The wheels are the single most expensive purchase made for this - much more (relatively speaking) than the frame.

Oddly the original brake caliper slots for the brake pads were longer, the brake pads with these newer 105 brake calipers just barely make it onto the wheel rims properly; I will probably file out the slot holes so that they can be moved a little to do a better job of gripping the rims. This I suppose is the problem with choosing parts from different eras in bike production practices.

The Shimano 105 rings and cranks (pedal arms)

The Shimano 105 rings and cranks (pedal arms)One change for me is that my other bikes have 172.5 mm long crank arms - these are slightly shorter at 170.0 mm. 170 is more typical of a (slightly) smaller bike. I don't have particularly long legs, so perhaps this is good?

Bridgestone company nameplate on headtube

Bridgestone company nameplate on headtubeSummary - the assembly of the parts (in effect, attaching to the frame in various ways) was not particularly difficult - the complex part was figuring out which parts from which periods would work together and also trying to order only parts that would fit with whatever had been purchased already. Not sure why, but it was quite enjoyable and best of all, the bike is fun to ride and looks lovely (says I). Getting used to the different shifters is a challenge but that's OK.