Let's Bike It проект по развитию велодвижения в России (Russian version) and Let's Bike It Russian cycling development project (English version). The English version is a completely different set of entries on the same topics in English. At the moment the two authors are traveling in Europe (France, the Netherlands) doing research on cycling (I suppose it is like research, anyway).

Live Streets or Живые улицы is not just about cycling but urban issues more generally, from Ekaterinburg. Russian only.

Iron Pony First is блог о велосипедной культуре в Петербурге, о которой пока что не так много можно сказать, поэтому приветы от других велосипедных культур здесь тоже будут. That is, a blog about bicycle culture in St. Petersburg (about which there isn't much to say for now . . . ). Russian only.

Cyclepedia.ru is an online Russian biking magazine, of sorts. Only in Russian. Has section for videos and various types of bikes, such as fixed gear.

When the first diamond frame bicycles became popular in the 1890s they were often called "wheels" - the national cycling association was called the "League of American Wheelmen." We have moved from "wheels" to "bikes," but the bicycles have remained remarkably the same over more than 100 years - elegant in their efficiency and simplicity. And many of the issues that we think are new? They were around then too.

Friday, November 12, 2010

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Alternatives to the "Traditional" Chain

Almost all bikes today have chains that are remarkably similar to each other and to chains of 100 years ago. All chains have pins that are 1/2 inch (and not some metric distance) apart - this means that it is fairly easy to check if a chain is "stretched" without special tools. (It isn't really that the chain stretches so much as that the pins bend, resulting in a longer chain.) Simply matching up a ruler to a straight length of the chain for 12 inches will show whether the chain is longer than it should be or not. If the chain is stretched more than a few percent longer than it won't match up with the teeth on the cogs and rings and can ruin them - and chains are cheaper than cogs and rings. If you let it go long enough, chains can break - I once saw a fellow break a chain while crossing 14th St on Independence in DC. Rather an abrupt stop.

I'm told that at some time in the 1990s Shimano introduced a chain with one centimeter between pins - the resulting links were closer together and of course the cogs and rings had to be with teeth that were also closer together. Like many "innovations" that represent a pointless departure from traditional approaches, it didn't catch on.

An idea that is presented as new but is actually from the 1890s is to replace the chain and rings with a drive shaft - in other words, before there were cars with drive shafts, there were bicycles with them. Wikipedia's article on bicycle chains notes that a bicycle chain is more than 98 percent efficient in transmitting power, so the big problem with other systems has been that they are usually less efficient.

This 1900 catalog has a shaft drive bike listed first:

At 65 dollars, the shaft drive bike is the most expensive model that this company was selling at the time. Presumably the big plus was that the shaft drive was cleaner than a chain, and for women didn't require netting over the rear wheel and chain guards to keep skirts out of the chain system. One suspects the absence of systems to demonstrate the lesser efficiency may have also contributed to a continuing interest in chain drives. Note that the drive shaft took on the role of the right side chain stay in the bike's structure.

For whatever reason, some early bicycle manufacturers pushed shaft drive bicycles for some time. They were even used by cycle racers - the African American rider Major Taylor rode shaft drive bikes in races, for example. But eventually they fell out of favor - for one thing, they were always more expensive than the comparable model with a chain. Also, removal of a rear wheel to work on a flat tire appears to be more complicated on a bike with a chain drive.

Notwithstanding all that, there have been attempts in recent years to introduce bikes with shaft drives, generally on bikes where the perceived lower maintenance and cleaner aspect of a shaft drive would be attractive, usually paired with an internal hub shift system.

In this modern example, there is a chain stay and the drive shift.

Another, probably more sensible approach is to use a drive belt to replace the chain. The belt is based on timing "chain" (or belt) technology developed for cars and these belts are incredibly strong - and require no grease or lubrication, so they stay clean. Ixi Bikes makes a small easy-to-disassemble (but not folding) bike with a belt. Trek makes several different full size bikes with belt drives, such as the District single speed, below. The belt drive seems to be pricey compared to a chain but is almost certainly just as efficient.

I'm told that at some time in the 1990s Shimano introduced a chain with one centimeter between pins - the resulting links were closer together and of course the cogs and rings had to be with teeth that were also closer together. Like many "innovations" that represent a pointless departure from traditional approaches, it didn't catch on.

An idea that is presented as new but is actually from the 1890s is to replace the chain and rings with a drive shaft - in other words, before there were cars with drive shafts, there were bicycles with them. Wikipedia's article on bicycle chains notes that a bicycle chain is more than 98 percent efficient in transmitting power, so the big problem with other systems has been that they are usually less efficient.

This 1900 catalog has a shaft drive bike listed first:

The superiority of bevel gears for power transmission in the bicycle has become established beyond question.Actually this is clearly not true, but the next statement about how well the shaft drive lasts (29,000 miles!) compared to a chain of those days was probably a strong favorable consideration.

At 65 dollars, the shaft drive bike is the most expensive model that this company was selling at the time. Presumably the big plus was that the shaft drive was cleaner than a chain, and for women didn't require netting over the rear wheel and chain guards to keep skirts out of the chain system. One suspects the absence of systems to demonstrate the lesser efficiency may have also contributed to a continuing interest in chain drives. Note that the drive shaft took on the role of the right side chain stay in the bike's structure.

For whatever reason, some early bicycle manufacturers pushed shaft drive bicycles for some time. They were even used by cycle racers - the African American rider Major Taylor rode shaft drive bikes in races, for example. But eventually they fell out of favor - for one thing, they were always more expensive than the comparable model with a chain. Also, removal of a rear wheel to work on a flat tire appears to be more complicated on a bike with a chain drive.

Notwithstanding all that, there have been attempts in recent years to introduce bikes with shaft drives, generally on bikes where the perceived lower maintenance and cleaner aspect of a shaft drive would be attractive, usually paired with an internal hub shift system.

In this modern example, there is a chain stay and the drive shift.

Another, probably more sensible approach is to use a drive belt to replace the chain. The belt is based on timing "chain" (or belt) technology developed for cars and these belts are incredibly strong - and require no grease or lubrication, so they stay clean. Ixi Bikes makes a small easy-to-disassemble (but not folding) bike with a belt. Trek makes several different full size bikes with belt drives, such as the District single speed, below. The belt drive seems to be pricey compared to a chain but is almost certainly just as efficient.

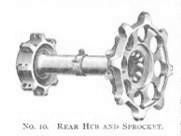

The Bicycle Chain - 1896

The technological improvements in modern bikes over those of the 1890s are much less than the 120 years would suggest likely. One of the critical "ingredients" for the first "safety bicycles" was the use of a chain to connect the rear wheel to a drive shaft with pedals (rather than pedals at the center of a large front wheel). The basic structure of a bicycle chain has not changed in all that time, but I was surprised to see that there were variations - the 1896 Victor Bicycle catalog (from Overman Wheel Co.) shows a chain where the sprocket teeth are spaced further apart and engage the chain only between every other (rather than every) link.

Commercial catalogs collection. Overman Wheel Co. Victor bicycles. 1896, University of Michigan.

Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015071455961

Perhaps the perceived advantage was that each of the sprocket teeth could be much more substantial, but the trade-off of having half as many teeth makes this seem a wash and somehow the symmetry of the chains we use today seems more efficient (and in any event, that chain won out). Would this approach mean that the pins would bend less? (That may have been a problem in those days.) And maybe the relative cost of chains was more than today so a sturdier chain for the money seemed wise. Hard to know at this distance in time.

Commercial catalogs collection. Overman Wheel Co. Victor bicycles. 1896, University of Michigan.

Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015071455961

Perhaps the perceived advantage was that each of the sprocket teeth could be much more substantial, but the trade-off of having half as many teeth makes this seem a wash and somehow the symmetry of the chains we use today seems more efficient (and in any event, that chain won out). Would this approach mean that the pins would bend less? (That may have been a problem in those days.) And maybe the relative cost of chains was more than today so a sturdier chain for the money seemed wise. Hard to know at this distance in time.

Monday, November 8, 2010

Cheap Spokes = Bad Idea!

My impulse buy bike, a Traitor Ruben steel sort-of cyclocross sort-of urban something-or-other bike had pretty good components but the wheels were no-name (other than the name of the company, Traitor) and the spokes were these black-coated anonymous things, 32 per wheel.

Anyway, a few months ago they started popping at the nipple end on the rear wheel. First one - replace it, then another - replace it. Now after the third has blown I have given up on one-at-a-time and am having the black crap spokes cut off and having the wheel rebuilt with new DT Swiss spokes.

A drive (ok, rear) wheel of a road bike with disk brakes has to work really hard, so the spokes need to be something other than junk selected to make the bike look "cool." (Assuming someone is going to ride the bike and not just admire it.) 2,000 miles or so isn't that long for the wheel to go through, so it is poor performance for the spokes to fail already. (No, I don't wait 220 pounds or carry panniers full of bricks.)

Well, there you have it. When evaluating a bike to buy, the wheels and the spokes should meet the same quality assessment as the derailleur (let's say). A 105 or Ultegra derailleur doesn't make up for crummy spokes.

Fiddlesticks!

Anyway, a few months ago they started popping at the nipple end on the rear wheel. First one - replace it, then another - replace it. Now after the third has blown I have given up on one-at-a-time and am having the black crap spokes cut off and having the wheel rebuilt with new DT Swiss spokes.

A drive (ok, rear) wheel of a road bike with disk brakes has to work really hard, so the spokes need to be something other than junk selected to make the bike look "cool." (Assuming someone is going to ride the bike and not just admire it.) 2,000 miles or so isn't that long for the wheel to go through, so it is poor performance for the spokes to fail already. (No, I don't wait 220 pounds or carry panniers full of bricks.)

Well, there you have it. When evaluating a bike to buy, the wheels and the spokes should meet the same quality assessment as the derailleur (let's say). A 105 or Ultegra derailleur doesn't make up for crummy spokes.

Fiddlesticks!

Saturday, November 6, 2010

Steel Bike in Morning

On my commute I sometimes am lucky enough to chat with some interesting riders. Friday I came upon a young fellow riding a 1985 Fuji steel racing bike that he had "restored" and somewhat updated.

This is a similar looking Fuji from that year. (I should keep my camera in a more reachable location when riding, I guess.)

The bike was beautiful - it looked new (well, other than the design) although he had removed all the decals so I had to ask him what it was. Very nice lugged frame and fork. He had reused the original derailleurs, shifters, and even brake levers. The one concession to modern cycling was to replace the so-called 27 inch wheels with 700 size that he hand built and to put on modern Campy dual pivot brakes.

I interested to see he was riding on 32 mm tires rather than 23 or some more racing bike-typical size. Hmmm. And he reported that while he had started putting in 80 PSI he was now closer to 60 and it seemed fine, speedy enough. And he obviously finds people like me, die hards in the "tires can't be too thin and have too much PSI" camp amusing. (23 mm and 120 PSI in rear, 110 in the front is what I have. I am rethinking this.)

This is a similar looking Fuji from that year. (I should keep my camera in a more reachable location when riding, I guess.)

The bike was beautiful - it looked new (well, other than the design) although he had removed all the decals so I had to ask him what it was. Very nice lugged frame and fork. He had reused the original derailleurs, shifters, and even brake levers. The one concession to modern cycling was to replace the so-called 27 inch wheels with 700 size that he hand built and to put on modern Campy dual pivot brakes.

I interested to see he was riding on 32 mm tires rather than 23 or some more racing bike-typical size. Hmmm. And he reported that while he had started putting in 80 PSI he was now closer to 60 and it seemed fine, speedy enough. And he obviously finds people like me, die hards in the "tires can't be too thin and have too much PSI" camp amusing. (23 mm and 120 PSI in rear, 110 in the front is what I have. I am rethinking this.)

Friday, November 5, 2010

No Bike Parking, Please (Capitol Hill, LoC)

How not very friendly. At the Adams Building, Library of Congress, Washington DC (on Capitol Hill).

What they mean is that they don't want bicycles locked to the railing blocking the ramp for the disabled, but do they provide a bike rack close by? No. Do they indicate where the nearest LC bike rack is (about 100 yards away, out of sight, across the street)? No. And so on. So instead people have bikes locked to sign posts up and down the street. Could be done better.

And the sign itself actually takes up more of the relevant real estate than any bike ever did. Oh well!

Thursday, November 4, 2010

Motor Scooter Parked as Bike

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)